Self-reported attribution doesn’t work. You need an attribution narrative instead.

Last updated: September 9th, 2022

Many SaaS companies struggle with attributing the results they get to the marketing investments they make.

A common scenario is that they’re paying a lot for qualified leads on a platform like LinkedIn Ads but they’re not really sure how important that investment is for their acquisition of new customers.

When this happens, they’ll do one of two things:

- Get frustrated looking at charts, tables and reports in various analytics or CRM tools

- Give up and buy into the popular narrative that attribution doesn’t work at all

Both of these outcomes are alarmingly common.

But they’re both flawed approaches that ultimately lead to an inability to make meaningful marketing investments or the argument that the marketing organization contributes to the bottom line at all.

We have frequently seen that companies fail at marketing attribution because they’re overly focused on a one or two data points and are more concerned with metrics than insights.

In this article, we’ll discuss:

- Why marketers struggle so painfully with marketing attribution

- Why the prevailing narrative that self-reported attribution is a panacea is extremely poor

- How to use an attribution matrix to build a better attribution model for your marketing activity

By the end of this article, you’ll have a framework to help you build an attribution model that works for your specific company so that you can make more confident investment choices

If you’d like help building a model for making better SaaS marketing choices, book a marketing plan session with our team and we can work through the problem with you directly.

Why marketers struggle so painfully with marketing attribution

For many marketers, even thinking about marketing attribution is a task they’d like to avoid.

In fact, whenever I ask a marketer what they struggle with most, it’s usually proving the ROI of their work – they know how it’s going but can’t point to the data that shows that.

Many people will try to use tools like Google Analytics, Google Data Studio or even reports on Hubspot or Salesforce to show the returns they’re generating through their work.

But no matter which analytics or reporting platform they use, they almost always run into a classic marketing technology (martech) problem:

Each platform has an inherent bias towards attributing conversions to whichever product they’re selling alongside analytics.

Hubspot reports, for example, always major on the impact of content and landing pages in your marketing.

Google Analytics obviously wants to tell you that paying them for traffic/leads through Google Ads is the best choice and so they use attribution models that favour their own product suite.

So it’s hard to even get a feel for how important any one piece of information or data might be when it’s gathered from a marketing product.

This deeply problematic issue is made worse by the fact that our data literacy is very low as a society.

Definitely not a personal indictment of marketers – because the problem is much broader than the marketing profession – it’s hard for us to really understand and question the data because we receive next to no formal education in data analysis outside of scientific or mathematical contexts.

Being able to find the response to a question like ‘how much traffic did we generate?’ is not the same skill as being able to answer a question like ‘how much impact did XYZ piece of content have on downstream revenue within ABC segment?’

It’s only natural then that the attitude towards marketing attribution is becoming more and more simplistic: data analysis and modelling is extremely hard.

But before we explain an easy model for improving, let’s just dive in and take a look at what happens when we simplify this in the wrong way.

Why the prevailing narrative that self-reported attribution is a panacea is extremely poor

At the start of the pandemic, it became increasingly popular to believe that the only really accurate way to work out where to invest was to ask people with an open form field and the question: “Where did you hear about us.”

A big driver and narrative around their argument is the point that I just shared: that martech vendors are incentivised to take credit for conversions or revenue and so it makes little sense to trust them.

The widespread use of this tactic was made possible by a relatively small number of LinkedIn influencers and their fans who viciously argue and ridicule anyone who disagrees – an extremely negative culture.

But niceness aside: this model is also extremely flawed.

Firstly, it assumes that leads are better at remembering your marketing than they may be in reality.

Your marketing strategy likely involves a handful of channels with multiple campaigns, content types and formats.

Even in a simple marketing strategy, there are dozens of ways that prospects can interact with you at different times.

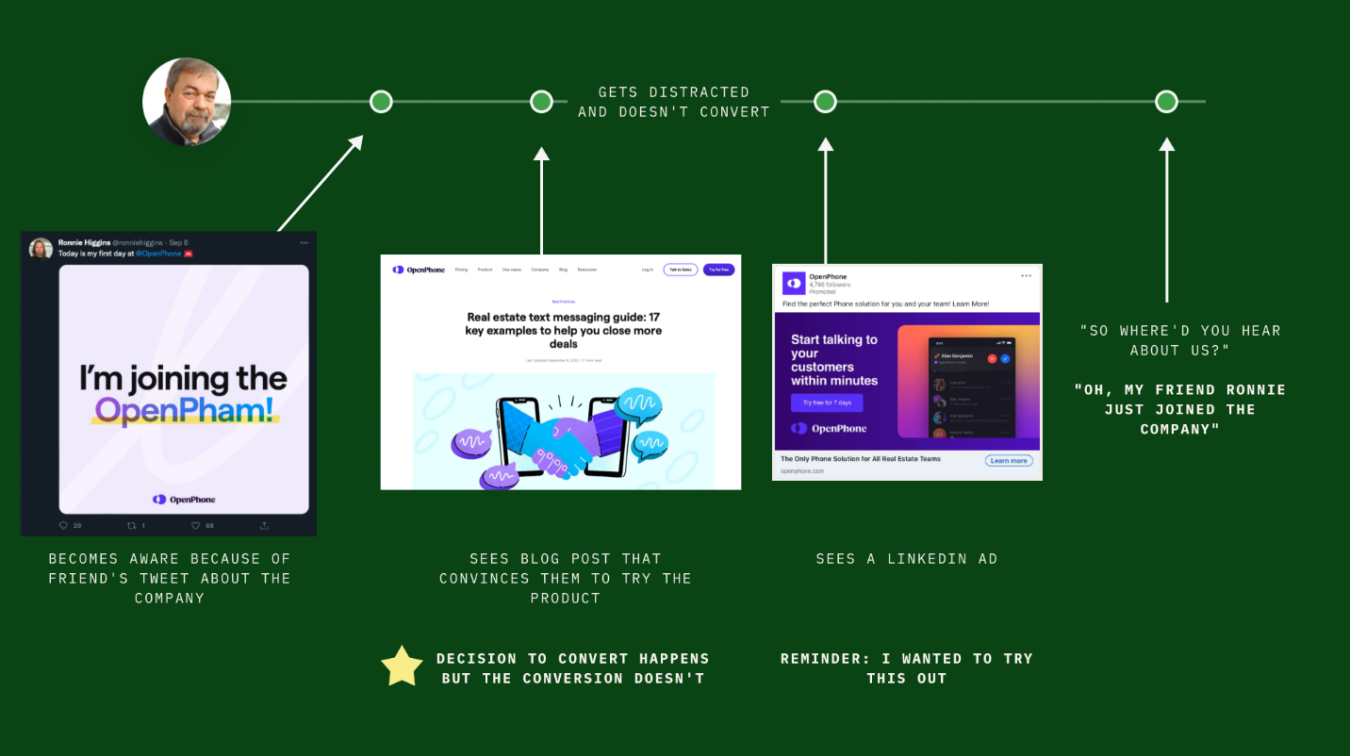

Taking a fictitious example here – OpenPhone don’t actually use the ‘where did you hear about us’ sign up because they have a more robust model of marketing attribution:

- My friend Ronnie announces on Twitter that he’s starting a new job at a company called OpenPhone

- So I click on his profile and check out OpenPhone’s website where I see a blogpost that speaks to a pain point I’m having: ‘examples of how people are closing more deals through SMS’

- I decide that I’d like to try their product and have a free trial – but then someone calls me and I need to talk to them so I forget about OpenPhone and go put out that fire

- A couple days later, I’m browsing LinkedIn and see one of OpenPhone’s ads. I go and check it out again and remember that I wanted to sign up.

- When asked, ‘Where did you hear about us’ I say: ‘My friend Ronnie just joined the company’

In this scenario, if I’m putting all my marketing investment choices into the answer to that one question, I’m going to just end up asking all my employees to start tweeting that they’ve joined the company.

But the reality is the conversion path is way more complex than that – and if I built my marketing system around the open field text box, I wouldn’t be able to send the traffic that Ronnie so brilliantly made aware of my product anywhere to convert.

After all, I wouldn’t have developed the content, or run the ad campaign that actually built the awareness.

Self-reported attribution is about as useful as a screen door on a submarine if it’s taken alone.

The second major flaw is that it ignores several cognitive biases such as recency bias.

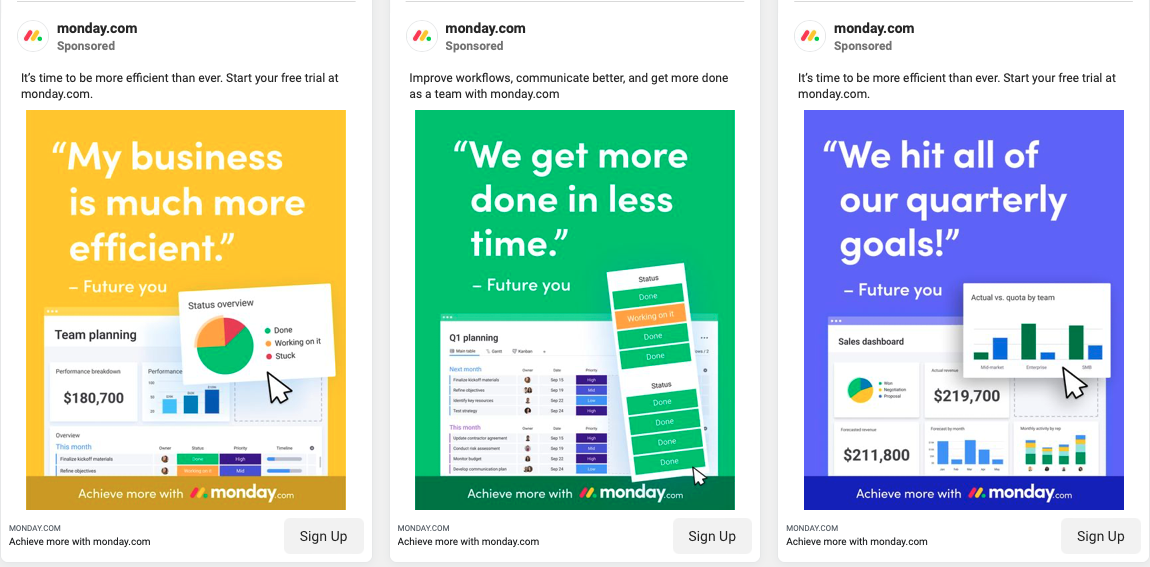

Take for example these Facebook ads that Monday are running at the moment:

Samples of ads that Monday.com runs on Facebook Ads

If you use Facebook, it’s extremely likely that you have seen one of those and so you know what Monday does and what it might be like to use the product.

But when I ask you in a form ‘where did you hear about us?’ a bunch of factors come into play:

The Recency Bias will likely cause your brain to believe that the place you heard about Monday was whichever one of these ads you last remember seeing – even if you’ve been seeing Monday’s content for month or even years.

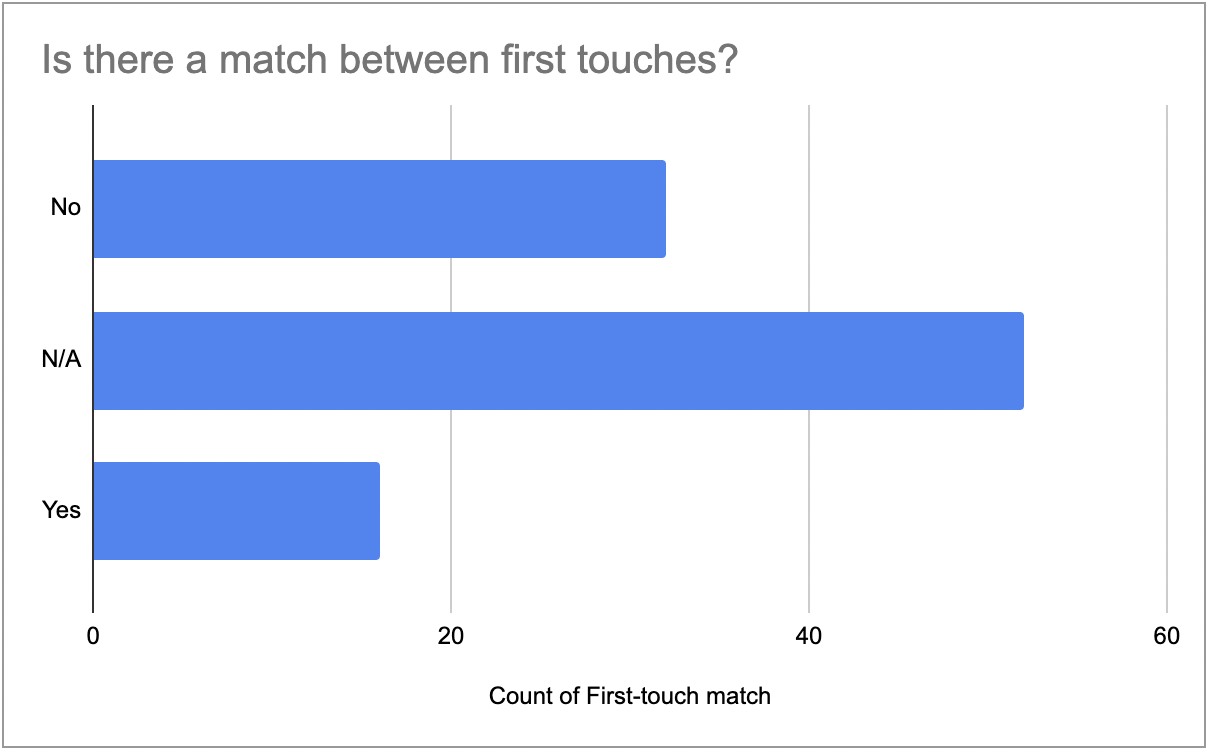

In fact, in a marvellously inventive test, Dreamdata found that leads were more often than not incorrectly reporting their ‘first-touch’ on a sample of 100 form submissions:

Source: Dreamdata

Source: Dreamdata

As a marketer asking this question, answers affected by the recency bias and taken at face value will only cause you to make flawed marketing investments in future.

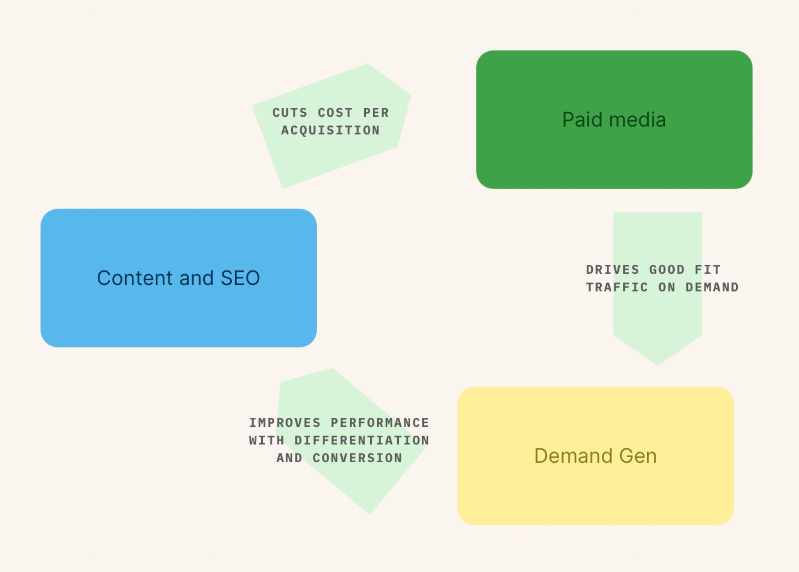

Finally, by solely relying on word of mouth attribution, you’re likely to stop investing in a healthy channel mix.

If your prospects are commonly influenced by content and SEO and tell you as much, you may think that you could stop investing in paid media.

But when you do that, you risk impacting the ability to drive good fit traffic on demand.

The inverse is also true.

If you remove content and SEO investments based on your understanding that most leads see an ad on Twitter and then convert (because they tell you directly) then you will find that your acquisition costs rise significantly.

A marketing mix tends to reduce overall costs because it recognises that demand rarely comes through a single channel.

Self-reported attribution is not a good model for decision making when building a SaaS marketing system. It leads people to myopic views of their own marketing investment.

While it may be significantly easier to slap a form field on your lead form and call it a day – this also leads to terrible impacts on your ability to make accurate choices about your marketing mix.

But if data from marketing attribution and reporting tools isn’t good and self-reported attribution is flawed, then how should marketers be making choices about their investment?

We think the answer is to use an attribution matrix to build a narrative around multiple data sources and in the next section, we’ll explain how to do that in practice.

How to use an attribution matrix to build a better attribution model for your marketing activity

Rather than thinking in terms of metrics and data points as holding the answer, it’s more useful to think about every data point as being a contributing detail to a data story.

In a story, there are fine and broad details as well as clear and unclear details. But no story is complete without a narrative to align all of that.

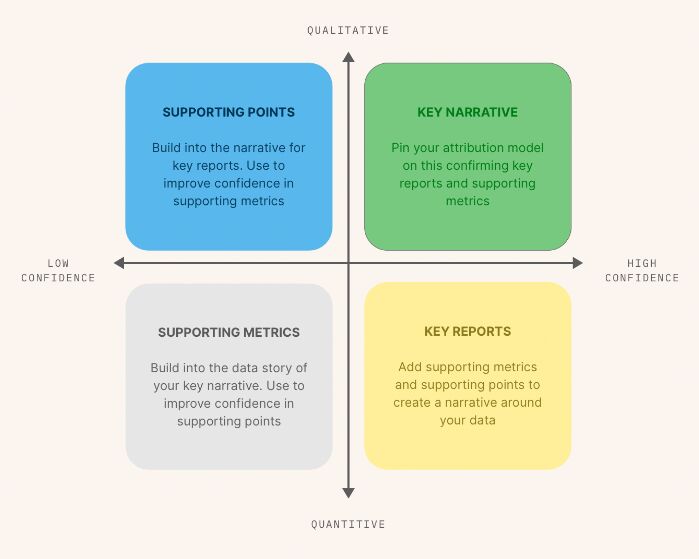

That’s why it’s useful to think about attributing impact of every marketing activity on a matrix where the axes are:

- Qualitative (not measurable by numbers) vs Quantitive (measurable by numbers)

- Low confidence vs High confidence

This is a much more natural way to assess a variety of different data sources because it takes into account the failures and successes of both qualitative and quantitive sources helping you to build a rich and flexible picture of your performance.

But how do we take all the information from the following sources and use them in reality:

- Ad platforms

- Web traffic analytics

- Social engagement

- Community engagement

- CRM data

- New, innovative or additional data sources that may appear in the future

Marketing attribution matrix

Realistically, you need a framework for classifying them such as:

- Key narrative – qualitative, high confidence signals – e.g. self reported on calls, demos and yeh, sure, form fields but also sometimes your own gut feel (you’re instinctively smarter than you think you are)

- Supporting points – qualitative, low confidence signals – e.g. comments on social posts

- Key reports – quantitive, high confidence signals – e.g. ad platform data

- Supporting metrics – quantitive, low confidence signals – e.g. engagement with email marketing

But it’s in the combination of multiple quadrants and sources on this matrix that the magic actually happens.

If I’m a marketer who tends to lean on qualitative signals (read: I actually do), then I know that in addition to the Key Narrative, I should add in Key Reports and Supporting Metrics to get a richer picture of what’s working and what’s not.

Whereas if I’m a classic quant, then I should take Supporting Metrics and Supporting Points and add them to my Key Report in order to test the quality of my reporting.

Combining models in this way makes sure that I no longer take a myopic view of my marketing investment.

I know that all of those activities count and can begin to build a narrative around what is working for our marketing and how important each piece may be.

For example and hypothetically:

- I may be able to directly counter qualitative feedback that our ads aren’t that important by adding in data around who commented on those ads

- I could add email marketing performance data to common entries on our self-reported form fields that say variations of ‘your blog posts are great’ to learn that it’s actually marketing automation and lead nurturing that drives the awareness of our blog posts in the first place

Now I have a data story about an individual lead or segment.

In closing

Marketing attribution is not black and white.

A common scenario is that they’re paying a lot for qualified leads on a platform like LinkedIn Ads but they’re not really sure how important that investment is for their acquisition of new customers.

When this happens, they’ll do one of two things:

It’s not uncommon to find marketers are frustrated with the data-heavy approach they’re taking because they can’t get the answers they want and end up turning to weak attribution models like self-reported attribution.

But this is a flawed approach that ultimately leads to an inability to make meaningful marketing investments or the argument that the marketing organization contributes to the bottom line at all.

Instead of just looking at one data point or one kind of dataset in a marketing attribution model, B2B SaaS marketers should move towards building a narrative around the combination of the following:

- Key narrative – qualitative, high confidence signals

- Supporting points – qualitative, low confidence signals

- Key reports – quantitive, high confidence signals

- Supporting metrics – quantitive, low confidence signals

Sure. Attribution is complicated and confusing. But don’t let a LinkedIn marketing guru tell you that you shouldn’t try to at least throw some quantitive light on the ‘dark’ room of your marketing investment

What you should do now

Whenever you’re ready…here are 4 ways we can help you grow your B2B software or technology business:

- Claim your Free Marketing Plan. If you’d like to work with us to turn your website into your best demo and trial acquisition platform, claim your FREE Marketing Plan. One of our growth experts will understand your current demand generation situation, and then suggest practical digital marketing strategies to hit your pipeline targets with certainty and predictability.

- If you’d like to learn the exact demand strategies we use for free, go to our blog or visit our resources section, where you can download guides, calculators, and templates we use for our most successful clients.

- If you’d like to work with other experts on our team or learn why we have off the charts team member satisfaction score, then see our Careers page.

- If you know another marketer who’d enjoy reading this page, share it with them via email, Linkedin, Twitter, or Facebook.